Designing effective writing assignments that tap into the specific learning objectives you have for your science classes is imperative if students are to benefit from their inclusion. There is an art to designing these, but the process is made easier by following a few best-practice guidelines, which are discussed in this podcast.

We hear from the Coordinator of UBC’s Writing Across the Curriculum program, and UBC’s Coordinator of the First-Year English program, who provide their top tips for designing writing assignments. They also discuss the types of writing assignments that work especially well and provide hints for encouraging students to really engage with these assignments.

We have created three complementary resources that may prove useful to instructors wishing to integrate writing assignments into their classes. The first of these provides a series of low-stakes writing prompts to help students get used to writing, while the second asks students to write a journalistic newspaper article based on the news within a published journal article. The third assignment will help students get into the habit of designing a writing outline before trying to write a long piece.

All of these come with suggested rubrics, which are available to download with the resources once you have contacted a site administrator here. Once you have provided your details (including a verifiable academic institution email address) you will receive a password that will enable you to download the rubrics.

Many students find it difficult to put their thoughts onto paper, and consequently put off starting a piece of writing for far too long. To help encourage them before asking them to complete lengthy writing assignments, such as essays or lab reports, it is a good idea to have them complete short writing assignments in class.

By completing one such writing task at the end of each week, students will begin to gain confidence in the writing process in a low-stakes environment. Each task, which should last for around 10 minutes, could ask students to either:

- Argue a position and defend it with logical reasoning, or

- Write about a topic recently discussed in class to reinforce content knowledge

Peer review, and improving written work based on feedback from others, goes hand in hand with science writing. To help instil this concept in your students you may wish to ask them to review their peers’ writing from the previous week as a way of kick-starting the current week. This will help review some of the previous week’s content and give them practice in providing useful feedback. If you ask students to provide short written critiques to their peers, it will also give them more writing practice.

Note: These tasks may also help you to monitor attendance throughout the course of a semester if you collect written answers at the end of class. You may also wish to attach a very small portion of the cumulative assessment for the class to these writing tasks to encourage students to make a real effort in their writing.

1) Arguing a Position and Defending it With Logical Reasoning

Example writing prompts:

In approximately 200 - 300 words justify, with at least three examples to support you conclusion, whether you would rather be:

- A polar bear or a grizzly bear.

- A top predator or a prey species in a jungle ecosystem.

- DNA or RNA.

- A specialist or a generalist.

- An ionic bond or a covalent bond.

2) Answering Content-Based Questions to Reinforce Class Topics

Example writing prompts:

In approximately 200 - 300 words:

- Give two examples of scientific breakthroughs that have changed the world, and assess how much of a difference they have made to modern life.

- Explain the difference between applied and basic research and provide two examples (one of each) that show why it is important that both receive funding.

- Explain how DNA is replicated and provide two examples of how it can occasionally go wrong.

- Give two examples of bacteria that have evolved resistance to antibiotics, and explain what we can do to reduce the risk of resistance developing in others.

- Explain how competition for resources can lead to organisms evolving specialist features, and provide two examples that illustrate this.

Click on this link to read a journal article published in the open-access journal, BMJ (British Medical Journal), on August 4, 2015 (doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h3942). You may wish to save/print your own PDF copy.

This research article was written for a specialist (medical science) audience. Note how it follows the I-M-R-A-D (Introduction – Methods – Results – and – Discussion) roadmap of a typical journal article. Given the interesting findings, and their implications, this research would be interesting to non-specialist audiences that would be unlikely to read it in this specialist publication.

Imagine that you are a science reporter and have been asked by your editor to write a short article (250 – 300 words) for the newspaper.

Style Hints – Developing Your Article

- Specific detail is important in journal articles; however, informal (even quirky) writing, without too many details (like those found in a science journal article’s methods section), is more likely to capture the imagination of the casual reader.

- Jargon should not appear in journalistic writing if at all possible. If you find yourself needing to include any technical jargon, make sure you explain its meaning in layman’s terms as well.

- While thinking about the best hook for your story, remember that telling a simple, easy-to-understand story is your goal. While a journal article may report many findings, it is usually best to focus on one for a newspaper-style article (try to choose the most newsworthy).

- If/when you do need to include something complex for a non-specialist audience, try to add in a descriptive simile or metaphor that uses an everyday example to help comprehension.

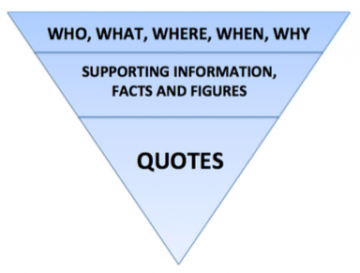

- There are many different ways of attempting to structure a journalistic article. One such approach is to include the 5 W’s (the who, what, where, when, why) in the first two paragraphs of an article/post. Journalists sometimes refer to this as the lead. Aim to write a lead in no more than 50 words.

- Develop the story with more specific information and quotations after the lead by working down the inverted pyramid of information (see below). Add to the story by including content of increasing depth and decreasing breadth.

- Include quotations from relevant sources to make the story more interesting and add a personal touch as well as credibility, but make sure these quotations say something useful. Try to ensure they add something to the story (they don’t just repeat information already paraphrased beforehand) and make sure they are interesting and easy to understand.

- Choose a quirky, snappy title for the article, to draw people in. Shorter is sweeter in most cases.

- Try to think of any relevant images that you would add to your article to boost readership. But remember to credit the source of any image, just as you would cite a source used in an essay or lab report.

Grading Criteria (Distribution of 25 Marks)

- 0 – 2 marks for your choice of a snappy, engaging, relevant title

- 0 – 3 marks for the succinctness and simplicity of your lead (include the 5 W’s)

- 0 – 3 marks for your choice and ordering of quotes (see below)

- 0 – 3 marks for limiting the use of jargon

- 0 – 3 marks for using a good simile/metaphor to explain something complex

- 0 – 3 marks for balancing some specific detail with the need for a simple story

- 0 – 3 marks for your choice of image (see below) and an appropriate caption

- 0 – 5 marks for the quality of your writing (logical structure, grammar etc.)

- Quotes (0-3 marks)

Remember to only choose quotes that add something interesting and/or relevant to the story. Four fictional quotes are listed below.

You may incorporate any/all of these, but you will be assessed on your choice and on the order in which you use them. Hint: You don’t have to use all of these quotes.

Nutritionist, Bailey Reilly, said: “This is really interesting but before we advise everyone to rush out to their local produce stores to stock up on chilies, we need to be certain this is not just an association and a real, cause-and-effect relationship.”

Thai restaurant owner, Naomi Wei, said: “This is no surprise to my family. The Weis have been eating chilies every day for generations and we generally live long, healthy lives.”

Nutritionist, Jonny Nolan, said: “This study showed that people who ate chili more frequently than others were significantly less likely to die within the study period.”

Associate Professor at Trinity Biomedical Centre, Yolanda Kennedy, said: “Because we are looking at a correlation only, I think it’s too early to say for sure that eating chili will help you live longer, but there are scientific reasons to think it might. For example, we know that chili can help break down fat, and high levels of body fat are associated with an increased risk of heart disease.”

- Image (0-3 marks) and caption

Try to find a suitable image to accompany your article. Once you have found it, insert a link to the image online (to reference where you found it) and write a suitable caption. Hint: Use the Google Images advanced search (click here for the link). This search option allows you to add a filter for usage rights (select free to use or share, even commercially) to make sure you do not infringe on any copyrights.

Are We Alone in the Universe? Writing Outlines Assignment

Whether you are writing a lab report, an essay, a journalistic piece or a scientific journal article, it is imperative that you plan before you put pen to paper or fingers and thumbs to keyboard; if you fail to prepare, you should prepare to fail!

Some people believe that producing a plan (or a writing outline) is a waste of time, thinking that valuable hours used this way could instead be spent on actually writing or editing the piece of work the outline is designed to guide. However, without a well-defined writing outline, it is surprisingly difficult to put your thoughts into text in a balanced, logical way, and this just makes the editing process even more of a headache. Ultimately, you will find that you save much more time by creating and using a writing outline.

There are three main stages to producing any piece of scientific written work. These are:

- Researching (finding, reading, and making summaries of interesting, relevant work to include in your writing)

- Writing (creating and using a writing outline, drafting and revision)

- Editing (cutting unnecessary content, tightening up grammar, adding in topic sentences and smooth transitions)

In this assignment you will focus on the first two stages as you plan how to write a balanced 600-700-word essay that answers the prompt: Are We Alone in the Universe?

Research – The Literature Search (15 marks)

Reading lots of relevant material is important to make sure you are able to present an up-to-date picture of the current thinking in the area of research you are writing about, but the more you read, the less you remember, and the less you remember, the more you forget! This is why it is vital that you make short summaries of work that you read, in case you wish to cite this material in your written draft. Even if you are working with a relatively small number of sources, you’ll be surprised how quickly you forget content, and how often you have to re-read articles when it comes to writing your piece.

In this assignment, you will need to compile a document that comprises four or five lines of information outlining the major content and/or arguments made by the author(s) of each article that you wish to cite in your essay. You will also plug some of this information into your writing outline in the second stage.

Before beginning, read our resource on finding sources for tips on researching the literature:

- Try to produce your document of written summaries for at least five primary or secondary sources that you would cite as part of your essay.

- Try to produce a balanced list (e.g. not just articles arguing only one side)

- Include full citation details of the articles, including the authors’ names, the year of publication, the article title, journal title, journal issue number, and page numbers. If possible, also include a link to the article if it is online.

Planning – The Writing Outline (Part I, 10 marks)

Aim to break down a plan into sections and sub-sections that will each need to be addressed in your essay. Think of the Contents page of a book: this is what you writing outline should look like, with each chapter (or paragraph) building on the one before and ‘signposting’ a change of direction in terms of content.

One of the most important parts of any outline is the logical development, which should help you write a balanced essay when it comes to putting pen to paper. In fact, without an outline, a writer may well include the same content but the final document will typically lack focus and read as though lots of information has just been clumped together. Remember this when putting your outline together, and ensure you link related elements together so that a reader could understand how you plan to build your case.

Planning – The Writing Outline (Part II, 5 marks)

Once you have your completed writing outline in ‘chapters’ form, you can start to plug in information from the material you summarized. You can do this in abbreviated form (e.g. bullet-points), but make sure you use some sort of coding system so you (and your instructor) know which source the information is coming from.

An Example Writing Outline

As a guide, the outline below was produced to help write an essay about whether planting native grassland plant species could help reduce the spread of a very invasive species (cheatgrass).

** You will need to use more development statements in between each paragraph (and state what these statements will be) to score highly **

** When it comes to writing an essay you will not cite the same information again and again, but should still indicate in your writing outline where the source of information has come from. This will help you decide where best to cite it initially in your essay, and may help you decide where and when you need to cite the same source further along **

1: Introduction

a) Thesis statement: Native species can suppress invasive species in Canadian grasslands but some are more effective than others.

b) Development statement: Outline what will be discussed, and in what order

2: Cheatgrass and Native Species

a) Biological information about cheatgrass (style of growth, lifespan, origin)

b) Biological information about common native species in Canadian grasslands

c) How native species may suppress invasive species (examples of competition)

3: Relevant Experiments

a) Lab-based experiments that tested whether cheatgrass can be suppressed

b) Field experiments that tested whether cheatgrass can be suppressed

c) Common findings:

i) Which species are successful at suppressing cheatgrass

ii) Which species are unsuccessful at suppressing cheatgrass

d) Other factors affecting success/failure (environmental factors)

4: Implications

a) What does this mean for conservationists trying to suppress cheatgrass?

i) Native species may be successful, but only in certain environments

ii) Some results are still unpredictable

iii) Sometimes other methods (such as controlled fires) may be needed

b) Which species and environments might see the greatest success?

5: Conclusion

a) Reiterate opening thesis statement to underline the argument made

The suggested rubrics for these activities require a password for access. We encourage interested instructors to contact Dr. Jackie Stewart and the ScWRL team to obtain access. Please fill out the Access Request and Feedback Form and then click here for the rubrics, which are housed on the suggested solutions password protected page once you have been granted access.